The “Wall of Separation”

There is much public confusion today over the phrase, “wall of separation,” in terms of describing the official relationship between church and state in the United States of America. Many conservative Christians, intent upon denying that the concept has any relevance in the founding of America (so as to argue that America was founded as a Christian nation), claim or infer that Thomas Jefferson coined the term a decade after the enactment of the First Amendment.

There is much public confusion today over the phrase, “wall of separation,” in terms of describing the official relationship between church and state in the United States of America. Many conservative Christians, intent upon denying that the concept has any relevance in the founding of America (so as to argue that America was founded as a Christian nation), claim or infer that Thomas Jefferson coined the term a decade after the enactment of the First Amendment.

In reality, however, the use of the precise phrase dates back to Roger Williams (illustration), the first Baptist in America, in the early 17th century. Williams used the phrase in 1644 (“Mr. Cotton’s Letter Lately Printed, Examined and Answered”) to describe the Baptist belief that church and state should be kept separate. A strong advocate of freedom of conscience, Williams’ insisted that the state should not intrude into the free exercise of religion, and that religion should be disestablished from government.

Why did Roger Williams want to build a “wall of separation” between church and state? From the fifth century through the Reformation, church and state ruled together, and the marriage consistently produced wars, destruction, killings, and intense persecutions of those who did not embrace state religion. Yet there was more. Williams realized, as had the first generation of Baptists before him (the Baptist faith emerged in 1609 in Amsterdam, Holland), that state religion – even in the guise of Christianity – was false religion. True religion, according to Baptists, was voluntary and came from a free conscience, as taught by Christ. State operated or approved religion, therefore, was the enemy of genuine faith.

Persecuted for his beliefs (and nearly to the point of death) by the Puritan (Congregational) state church of New England, Williams purchased land from Native Americans and founded Providence Plantations (now the city of Providence, Rhode Island) in 1636, and eight years later was instrumental in the establishment of the colony of Rhode Island.

Providence, initially, and then Rhode Island, were founded on the principles of freedom of conscience, full religious liberty, and separation of church and state. The rise and advocacy of these principles was a radical development in the history of colonial America, and Williams and his fellow Baptists in particular were considered, by other Christians, to be liberals, heretics, and infidels.

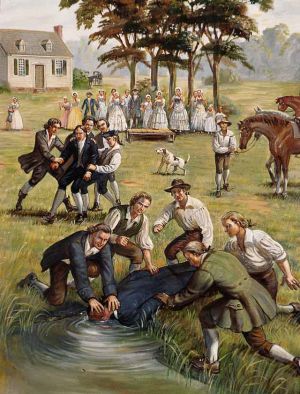

The generations of Baptists in America who followed Roger Williams continued fighting for the separation of church and state. Christian government officials in both the northern and southern colonies persecuted the heretical sect. Baptists, who refused to pay taxes to the state church and refused to baptize their infants (as the law required), were beaten, whipped, jailed, stoned, shot, waterboarded, and had their lands confiscated. In some cases, church state officials accused Baptist parents of child abuse for not baptizing their infants into the state religion, and in punishment took their children away from them.

The generations of Baptists in America who followed Roger Williams continued fighting for the separation of church and state. Christian government officials in both the northern and southern colonies persecuted the heretical sect. Baptists, who refused to pay taxes to the state church and refused to baptize their infants (as the law required), were beaten, whipped, jailed, stoned, shot, waterboarded, and had their lands confiscated. In some cases, church state officials accused Baptist parents of child abuse for not baptizing their infants into the state religion, and in punishment took their children away from them.

The persecution of Baptists was not isolated. Between 1768 and 1776, roughly one-half of all Virginia Baptist preachers served time in jail for preaching in public, refusing to pay taxes, or otherwise defying the theocratic Anglican government in Virginia. In the painting above, Virginia Baptist minister David Barrow is being waterboarded in 1778 by Virginia’s church-state officials, for his heretical views.

In the 1770s, as America rebelled against Great Britain, most colonies were yet ruled by church states. Even as colonial governments and politicians proclaimed political freedom from England, they denied religious freedom to Baptists.

Yet, Baptist patriots proved valuable in the fight against Great Britain, and soon Baptists in Virginia were able to acquire new, powerful allies in the fight to separate church and state. Among their allies were Virginians James Madison and Thomas Jefferson. Virginia Baptists, most visibly represented by the popular evangelist John Leland, worked alongside the efforts of Madison and Jefferson to secure Jefferson’s 1786 Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom, which separated church and state in colonial Virginia and secured religious liberty for citizens.

Five years later, in 1791, American Baptists’ nearly two centuries-old campaign for church state separation was finally realized in the enactment of the First Amendment of the Bill of Rights to the United States Constitution. Stating that “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof,” the United States became the world’s first secular nation by enacting the Baptist vision of a “wall of separation” between church and state. As Baptists had long advocated, the First Amendment forbade government from interfering with religious expression (free exercise clause) and forbade the government from establishing or incorporating religion into government (establishment clause).

By 1833, thanks to the still tireless efforts of Baptists, the last vestiges of church state union at the state level were finally eradicated (Massachusetts was the last state to do so).

While Baptists of the late 18th and early 19th centuries – no longer persecuted by church state officials – rejoiced in living under a secular government in which church and state were legally and effectually separated, many conservative Christians (of former official state churches) remained opposed to America’s secular government, and insisted that God would punish America.

Most Christians of the founding era of America understood that the primary Founding Fathers (with one exception) were not Christian in the traditional sense of the word. In the larger context, few Americans (about 10%) attended church in the 1780s, and the primary Founding Fathers were no exception. Indeed, most of the primary Founding Fathers were deists (that is, they philosophically embraced a concept of a distant deity or supreme being, but rejected the divinity of Christ and the Bible).

If one enlarges the definition of “Founding Fathers” to include dozens or even several hundred prominent men who played various roles in the establishment of the American nation, the number of Christians (measured by affiliation) increases, as most were representatives of or leaders within theocratic colonies/states.

That the founding fathers resisted intense pressure by church state leaders to include references to God and Christianity in the U. S. Constitution, and then enacted separation of church and state in the First Amendment, did not sit well with many Christians who once had been the recipient of special government privileges. (Modern attempts, by conservative Christians in America, to reconstruct the primary Founding Fathers as evangelical Christians would have baffled conservative Christians of the late 18th century.)

Thomas Jefferson, by virtue of his prominent role in paving the way for the enactment of separation of church and state in the First Amendment (modeled after Jefferson’s 1786 aforementioned Virginia Statute of Religious Freedom), came to be especially despised by many conservative Christians of the early 19th century.

While Baptists greatly appreciated Jefferson (who in 1802 wrote a now-famous letter of response to praise from and a petition of Danbury Baptists of Connecticut, voicing the Baptist “wall of separation” metaphor to describe the First Amendment’s separation of church and state), many other Christians considered the president a heretic, infidel, and even an atheist.

Today, many conservative Christians place their faith in the myth that America was founded as a Christian nation, arguing that since the words “wall of separation” of church and state are not mentioned in the U. S. Constitution, the concept does not exist.

American Christians living in the 1780s and 1790s would have considered this argument to be ludicrous. They, living witnesses to the founding of America, well understood that America was established as a secular democracy with the separation of church and state (although not all appreciated this state of affairs).

_____________________________________________________________

Online Resources for Further Reading:

Religion and the Founding of the American Republic (documents from Library of Congress)

An Analysis of the “Founding Fathers” (by Bruce Gourley)

Religious Liberty and Separation of Church and State Quotes (by Bruce Gourley)

Top Five Myths of the Separation of Church and State (Baptist Joint Committee For Religious Liberty)

History of Religious Liberty in America (First Amendment Center)

An Outline of Baptist Persecution in Colonial America (Bruce Gourley)

The Religious Liberty Archive (an excellent collection of primary documents)

Suggested Books for Further Reading:

The Bloudy Tenet of Persecution, For Cause of Conscience … (by Roger Williams, 1644; edited by Richard Groves, 2001)

The Writings of the Late Elder John Leland

Liberty of Conscience: Roger Williams in America by Edwin S. Gaustad

Christian America and the Kingdom of God by Richard T. Hughes

Wellspring of Liberty: How Virginia’s Religious Dissenters Helped Win the American Revolution and Secured Religious Liberty by John Ragosta

Endowed by our Creator: The Birth of Religious Freedom in America, by Michael I. Meyerson

First Freedom First: A Citizen’s Guide to Protecting Religious Liberty and the Separation of Church and State by C. Welton Gaddy and Barry W. Lynn